Lying: A Milestone in Brain Development?

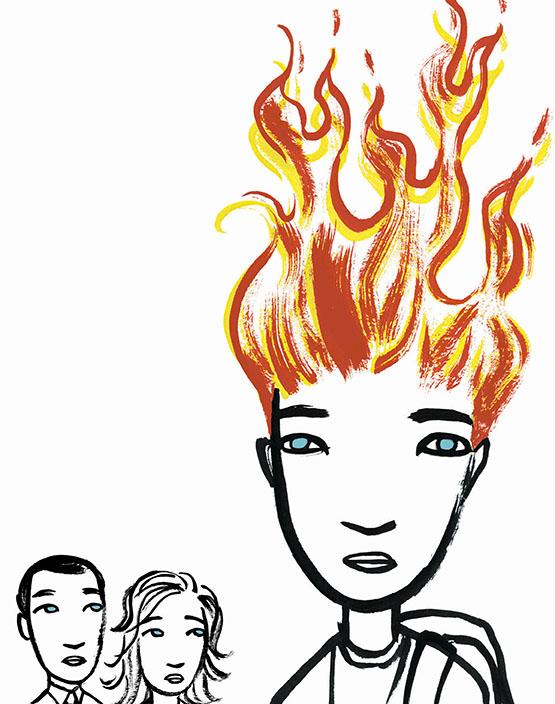

Michelle Kumata / The Seattle Times 2006

It is generally accepted that parents are responsible for teaching their children right from wrong. One of the most important values parents teach is truthfulness; in a study by Macquarie University of Sydney, children rated lies about wrongdoings worse than the wrongdoings themselves.

However, in light of recent research that correlates lying to neural development, perhaps lying should be – not rewarded, per se – but celebrated.

Specifically, children who are able to lie and maintain the lie exhibit larger working memories, better impulse control, and a greater understanding of the people around them.

To understand why this is the case, it may help to look at some different “stages” of lying that children go through.

As described by the National Institute of Health, the first “stage” of lying is fittingly called “primary lies.” These are usually told in an effort to avoid punishment and begin to appear around 2-3 years of age.

Primary lies tend to be marked by three characteristics:

They’re not very common (in one study, only half of children in this age bracket lied about having looked at a toy).

The consistency of statements over time tends to give the lie away. This is called semantic leakage.

Most importantly, the liar does not take into account the people to whom they are telling the lie or any evidence surrounding it that might contradict his or her version of the facts.

Around a year after primary lies are first formed, “secondary lies” begin to appear. They are quite similar to primary lies, but with two key differences:

Secondary lies appear much more frequently (90% of children in the age bracket of 3-4 years lied under the same circumstances as before).

They only occur in children who have the ability to understand what others are thinking. This ability is called “first-order theory of mind” and comes up frequently in deception science.

Finally, when children reach the ages of 7-8, they begin to exhibit “tertiary lies.” These lies are told using the same “strategies” of lying that adults exhibit.

The largest difference between secondary and tertiary lies is that tertiary lies involve the inhibition of semantic leakage.

This transition is marked by the acquisition of a “second-order theory of mind,” which is the ability to not only understand what someone else is thinking, but what they think about others’ thoughts as well.

Both of these transitions involve using much more working memory than was required for the previous two types of lying.

Given this, it might be expected that children who exhibit these different types of lies are in fact showing greater cognitive development. This is exactly the case.

In the same study mentioned earlier, all children took an executive functions test after either lying or not about peeking at a toy. Those who lied tended to score higher. Researchers found that for every point higher a child scored on this test, he or she was on average five times more likely to lie.

In a separate study, greater amounts of lying was correlated with greater impulse control.

Lying is still arguably not a behavior that should be encouraged. However, it is important to remember that when a child lies (at least for the first time), it is truly a developmental milestone.