One Man Faces the Chinese Communist Government

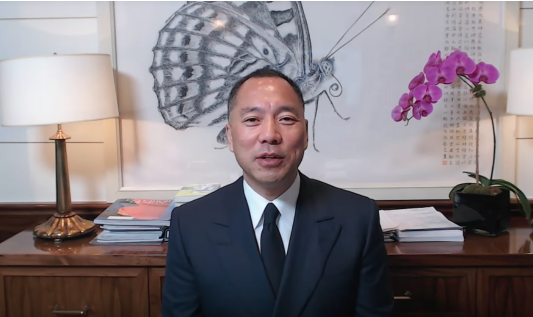

Miles Kwok from one of his YouTube videos.

During the summer, after coming home from camp, I frequently saw my mother focused on her computer. She watched YouTube videos of a Chinese man sitting in front of the camera, talking passionately to the screen.

He would go on for hours echoing through the first floor of my house, and I learned to drown his roaring voice out. But his name would be soon stuck in my head, and it was Miles Kwok.

I decided to figure out, piece by piece, who this man is. He is also known as Guo Wengui, and he is a self-made billionaire, currently hiding in New York City from the Chinese government. Through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, Kwok reveals corruption in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), such as in his hour long videos on his YouTube channel which my mother faithfully watches.

He often speaks while running on his treadmill or eating breakfast on his yacht, which I find amusing.

Through his close connections to the Ministry of State Security and other spy organizations, he discovered many government secrets. In a summer Washington Free Beacon report, Kwok reveals that China kept 10,000 to 20,000 spies in the U.S. before 2012.

After President Xi’s 2012 election, which my parents grimly say is not an actual, fair election, 5,000 more spies traveled to the United States, coming as students, businessmen, or immigrants. From defensive spying, the focus shifted to “offensive” spying.

Kwok informs that Chinese intelligence have four objectives: securing technology related to military weapons, bribing senior U.S. officials, bribing the families of political and business elites, and hacking the internet system. These spies, unafraid to do dirty work, could be anywhere.

In Kwok’s videos, his favorite victim is Wang Qishan, the head of the Chinese anti-corruption campaign and part of China’s highest decision making body. Kwok tries to prove that Wang, who is powerful and close to President Xi, has the duty to eliminate corruption but is deep in scandals himself.

HNA, a Chinese airline company, has recently grown at a suspiciously rapid pace, and has made many influential moves in the business world. Hard digging found that many of Wang’s family members are involved. For the past few months, Kwok continuously posted on Twitter how the Wang’s family benefited from hidden shareholdings from HNA.

During the summer, Kwok also released Wang’s wife’s social security number and passport number to his viewers, proving that Wang’s wife is either a citizen or a permanent resident. A rule states that families of Chinese officials cannot have citizenship or a green card. His wife has broken the rules of the Communist party, but it is doubtful that Wang’s political position will change.

In May of this year, two security officials traveled to the U.S. to pressure Kwok into silence. They attempted to convince the Trump administration to send him back to China as well. However, the FBI arrested one of the officials for violating visa rules and took his phone and computer. They had been threatening Kwok, his family, and business associates by phone and during meetings in Washington and New York.

In September, Miles Kwok applied for political asylum in the United States. This position that he has placed himself in is very dangerous, and the CCP is eager to keep him under control.

To The New York Times, his lawyer, Thomas Ragland, said that he is “a political opponent of the Chinese regime.” An asylum, or even a pending one, will protect him more than a visa would, which can be cancelled. Chinese prosecutors hope evidence they find will convince the U.S. to revoke his expiring-soon visa. They are trying to build a case against him, accusing him of at least 19 crimes such as bribery, kidnapping, fraud, and money laundering.

His increasing popularity and asylum application comes close to an important congress meeting for the CCP occurring recently. The once-every-five-year meeting determines new leadership positions and the direction of China for the next five years. Kwok’s claims and evidence could affect the positions of the people he accuses of corruption, especially since a focus of President Xi Jinping’s for past five years was fighting corruption. However, nothing is expected to change in the grand scheme.

News organizations pride themselves on proclaiming the truth and keeping power in check, but when it comes to China, its seems that things get a little shaky. In April of 2017, Kwok was supposed to give an interview for the Voice of America, but after an hour and 19 minutes, the broadcast was cut short.

A few days before, Chinese officials had met with a VOA correspondent in Beijing, pushing to stop the interview. They indicated to the impact it could have on visa renewals for VOA reporters going to China and other signs of favoritism China often showed to VOA. Someone higher up got nervous.

In October, the Hudson Institute, a think tank in Washington, planned a meeting for Miles Kwok. One day before the event, they cancelled. Unlike VOA, the Hudson institute acknowledge that they were pressured by China. Their website was hacked and could be traced to Shanghai.

Facebook blocked his profile as well and claims that his pages revealed personal information, violating their policies. For months, they have looking to spread to China where the largest population of people live and where Facebook is still blocked. Because of business interests, they are afraid of ruining their relationship with the CCP.

As much as the idea that the CCP has a new rival appeals to many people, some are not convinced. Kwok has not named sources or used definite evidence for his accusations. However, the CCP is not so innocent either: the government beat its enemies by ensnaring them into scandals that is easily supported by Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.

Kwok is using the same method. He attacks his opponents with allegations, hoping people will listen to him from outside of China and act. Kwok’s ways of releasing his statements seem unethical and his reliability seem suspicious, but in the current situation, the content of what he is saying does not matter.

Chinese protesters need the symbol of him, a firebrand that is not afraid of fighting fire with fire. Kwok is no hero, but he could possibly start a long chain of rebels and protests in the future.

Maybe people from other countries, such as us in America, can learn from him. I hope the right to protest will be recognized and endure through time.

Enya Xiang '21 is thrilled to return as Opinion Editor, this time co-editing with Sammy Biglin! She is excited to see what controversies and 'hot takes'...