Harriton Needs Sleep and Here’s Why

Wikimedia Commons

Biiiingggg rings the bell.

You’re relieved you made it to school on time. The teacher asks a question, and the classroom is completely silent. A few heads are nodding. You feel like a character in a Charlie Brown cartoon.

At some point, you realize these are not nods of understanding. These are your fellow classmates, dozing off to sleep in broad daylight. Welcome to the first period.

Sound familiar? Join the club, friend, for you are in good company. Recently, I took the time to ask a few 9th and 10th grade Rams a couple questions: “How do you feel when your alarm clock goes off? How are you doing at school with the amount of sleep you are getting?”

The answers were at best candid, and at worst required a bit of editing to suit The Banner’s obscenity filters. I personally would love more sleep, but I had no idea that such simple queries would unleash such tsunamis of vulgarity.

“Morning was created by Satan to punish the unworthy and I most certainly fall into that category. I HATE mornings and I can barely move until the middle of the first period.”

“I do go to sleep early, but I just can’t fall asleep.”

“Seriously?! I go between, ‘Sleep is for the weak’ and ‘I could sleep for a week!'”

“[I’m] super tired in class from nightly lacrosse and basketball (and TSA on Wednesdays). Also, I have yawned every day when saying the pledge … and I can’t help it and it’s creepy…”

“I’m already burning out, and I’m only in 9th grade.”

“I space out a lot and I have some trouble focusing and keeping my filter on. I don’t consciously feel too tired, but I let a lot of [stuff] slip.”

“My mornings are really slow… And I’m always yawning during the first set… And I have to set three alarms to wake myself up…mornings are NOT my favorite; I concentrate better at night.”

“When my alarm goes off it’s a big struggle to get out of my bed.”

“I go between feeling stressed out to feeling blue, way more than I used to in middle school.”

Blue is not only the mood of sleep deprivation, it is also the color of sleep deprivation. While some say we are not sleeping because we are over-scheduled (cue: sports, jobs, hobbies, social lives, babysitting, and homework), others accuse us of spending too much time on laptops, with their dreaded blue light.

The color blue is key, as it regulates the secretion of melatonin, which is the hormone responsible for getting us to sleep and keeping us there. Dim light turns on melatonin, and blue light turns it off. Blue light from screens hits cells in the back of the eye (the retina) called ganglion cells, which release a chemical called melanopsin.

This signal travels back into the brain, triggers the body’s clock, which then causes a small structure called the pineal gland to turn off melatonin production. To get melatonin to release the way it should means staying off of electronics before bedtime.

But most of us were using electronics in middle school and were able to fall asleep by 10:00 PM without issues. Now, most of us struggle to feel drowsy before 11:00 PM, screen or no screen. This is no accident but a direct result of the timing of melatonin release, which shifts in teenagers to a couple of hours later, forcing us to stay awake later and making early bedtime seem ridiculous for most of us.

How many of us can fall asleep at 8:00 PM, to get our 10 hours of sleep, even if we are dog-tired and dozing during the first period? Impossible! At least, with our circadian rhythm set up the way it is. So says Dr. Wendy Troxel, a Senior Behavioral and Social Scientist at the RAND Corporation and Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Troxel spoke recently during Sleep Awareness Week at an open symposium at Radnor High School called “Snooze or Lose: Sleep Health in Adolescents.”

“Two out of three adults get good sleep, but only 1 out of 10 teens do,” Dr. Troxel asserts. She refers to the advice by the Centers for Disease Control, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other professional organizations, that adolescents need 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night.

As Harriton senior Melanie Metz wrote recently in an earlier issue of the Banner, getting 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night is impossible when we have our biological rhythm forcing us awake late into the night, and a class start time of 7:30 AM forcing us awake early in the morning. It’s simple math.

We never get used to sleep deprivation. Instead, like money in the bank that is overdrawn, we continue to accumulate sleep debt when we go night after night sleeping less than the recommended amount.

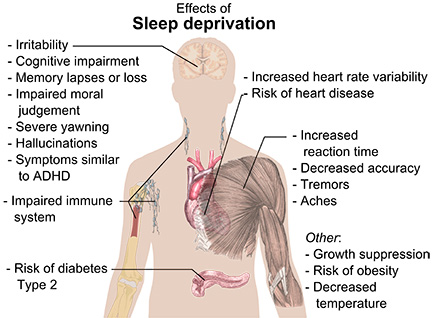

Sleep is important in many brain functions, including critical thinking, memory formation, processing emotions, impulse control, judgment, paying attention, solving problems, being alert, and motor speed. These functions are essential to our academic success, navigating relationships, and importantly, driving.

The group that is most likely to suffer a crash due to falling asleep at the wheel is the 16-25 age group. Sleep-deprived teens are also more likely to gain weight and use more alcohol or drugs than well-rested teens. Accidents and suicide, which are among the top causes of death in teens, are directly impacted by sleep deprivation.

Scariest of all, in 1995, Dr. Allan Rechtschaffen’s studies on rats showed that when deprived of sleep, the animals died within just two weeks. Thankfully, we are not rats. But we are not immune to the ill effects of chronic sleep deprivation, either.

“Sleep problems are a symptom of virtually every known mental disorder,” says Dr. Troxel.

So what can we do? We must focus on the areas where we have control. This means managing our sleep hygiene, which refers to a set of behaviors that help promote good sleep: limiting caffeine, getting exercise, eating healthy foods, turning off electronics in the late evening/night, and managing time efficiently.

However, even if we do all this expertly, professionals like Dr. Troxel say that, given our biological rhythms, getting sufficient sleep will not be possible, unless school start times are also delayed, so that our school schedules are in sync with our body rhythms, allowing us to operate at our “circadian sweet-spots,” according to Dr. Troxel.

District after district (Fairfax County, Ridgewood High School, Phenix City, Palo Alto, Campbell Hall, etc.) that delayed start times in middle and high schools to 8:30 am or later saw numerous benefits.

Moods lifted. Some saw test scores improve, including SAT scores. Tardiness and absenteeism went down. Driving accidents declined. Headaches, stomach upset, and anxiety decreased. That horrible morning brain fog lifted, and fewer students reported falling asleep during class. Even performance in sports is expected to improve. (Yes, perhaps good sleep will finally end the Ram football curse!)

As hesitant as many people are, implementing such a big change — which involves, after all, changing bus schedules, coordinating district-wide sports schedules, babysitting, and jobs — requires dedication to solving the problem. The districts that have buckled down and gotten the job done have not gone back to the old system, and it doesn’t seem like they will anytime soon.

Contrary to public opinion and fears, students in these districts have not simply stayed up later and continued to sleep less, but they have actually gotten more sleep, after all, because the later start time is better aligned with their biological clocks.

Our school is like many others, filled with sleep-deprived students. We survive in a culture that devalues sleep, insisting it is “for the weak,” and that we need to prepare ourselves for the real world.

Yet do we brag similarly about not needing oxygen, food or water?

As Dr. Troxel says, “Would we tell our toddlers not to nap because we are preparing them for kindergarten?”

If we stop and pay attention to the science and follow the lead that many other schools have set, delaying start times and allowing students to get sufficient sleep is completely possible. And having a healthy, happy, well-rested high school experience, even in the first period, can be our daily reality, instead of just a distant dream.

And now, speaking of dreams, it’s way past my bedtime, so I’ll say good night! You can read more about student sleep at Start School Later.

Anya Jayanthi '21 is thrilled for her fourth year with The Banner! As a co-editor for the S&T section, she hopes to continue exploring the greater...