The Soft Power of Dr. McKenna

Dr. Paul McKenna settles on top of a student desk, his feet perched on the hard plastic seat and right arm draped over the body of his guitar. It must be someone’s birthday—but a bad day is a good enough reason as well. The strumming begins coolly, and his voice, folksy and easygoing, drifts lightly through the room.

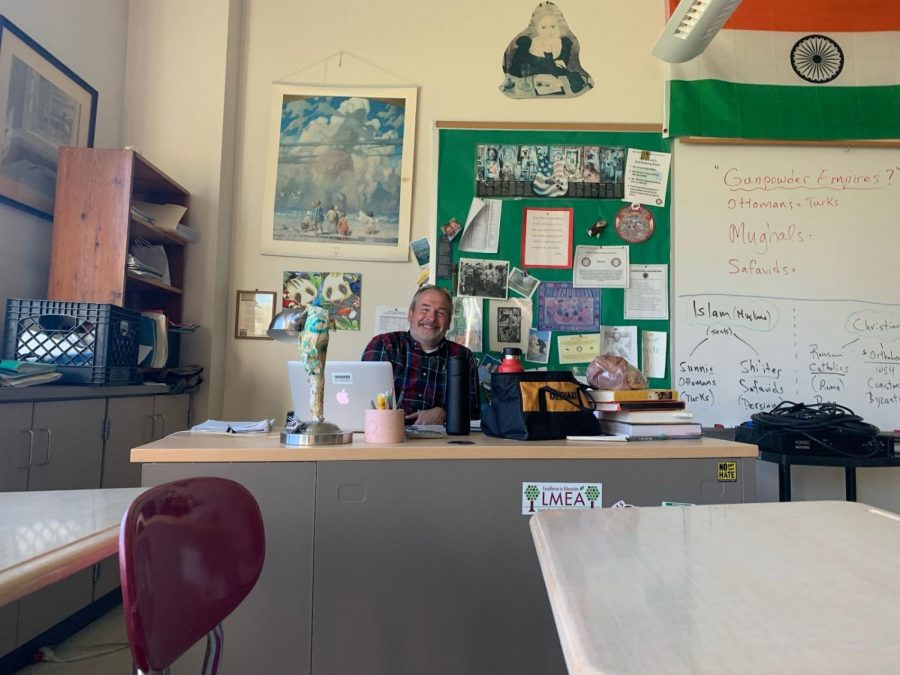

When unplayed, the guitar sits in its stand like a sentinel near the door of Room 107. Dr. McKenna, history teacher at Harriton and chair of the Social Studies Department, sits at a desk to the far right corner, sharing the room with Mr. Warren. Several water bottles, history textbooks, and a little etched clay cup crowd his desk. Behind him, the bulletin is decorated with postcards, notebook paper art, a Goethe quote, and a Teddy Roosevelt finger puppet.

In the story of Dr. McKenna, both history and the guitar are recurring motifs. “I stuck out in my history classes because I was this guitar-playing kid,” he laughs. “I spent a lot of time in the basement as a kid.” He would have a guitar at hand and the turntable close by. He lowered the tonearm to play the track—likely a riff from the Allman Brothers Band or Grateful Dead or Led Zeppelin. After a few seconds of concentration, he would stop it and attempt to replicate it.

All students know that a teacher can make or break a subject. An educator can sour a subject matter completely or make a whole classroom unbearable. When I entered Room 107 last year for IB History of the Americas HL, I was recovering from a bad experience with history. The study of the past appeared antiquated, frozen by tradition and unwelcome to outsiders. However, Dr. McKenna’s classroom dissolved these suspicions, and what began this was the simple fact that he loves history.

Dr. McKenna describes a time his wife questioned why he enjoyed the stories of World War II so much. He tells me what he said: “I don’t like the fact that sixty-some million people were slaughtered needlessly. I like the fact that we came out of it. Look, we came out of it! Humanity prevailed.” He pauses, but he has not completed his thought. His blue eyes concentrate with gravity as if he wants to make sure what he says is exactly what he means. “You find decency if you look for it.”

Dr. McKenna’s parents themselves were products of the Great Depression and World War II, defining moments of the 20th century. Their connection to a historical narrative as well as the humility that characterized that generation left an impression on him. “They lived in so many brutal moments that living in the movement you could really extract the joy from the moment when it was there,” McKenna said. “They took strength from that.”

While Dr. McKenna ultimately majored in History at Penn State, education had not been his initial goal. He debated about going to law school, but after working briefly at a firm, realized that it was not for him. He got a teaching job for court-adjudicated youth. Adjudication is the legal process that determines if a juvenile committed an act for which they are charged, “adjudicated” being analogous to “convicted.” He found that he liked it and stuck to education, going on to earn a Ph.D. in Education at Nova Southeastern University.

But before arriving at Harriton, McKenna taught in a juvenile detention center. It was low-wage and tough work. Recidivism rates were high, and youth regularly entered and returned. Some juveniles would get arrested because they simply wanted to come back to a place where people cared about them. Landing in the Lower Merion School District, therefore, felt like incredible luck, a situation where he could do something he cared about and make a living wage.

As much as the polished Harriton learning environment differed from the education services of the juvenile justice system, he discovered that certain themes remained true and transferable when he worked with students. “Kids are kids,” he said. Another thoughtful pause. “They want to be respected, and they want to be challenged, and they want to be valued. Some showed it in strange ways. Understanding that and not taking things personally I think is really important as a teacher.”

The systemic inequalities of America often sit at the intersections of class and race, and education disparities continue to stain the promise of equal opportunity. Lower Merion spends around $26,422 per student, while across City Avenue, Philadelphia School District spends about $10,000. Witness to the injustices in his field, Dr. McKenna has a sense of gratitude for what he has at Harriton. “I feel lucky that I’m teaching here,” he confides. “But should it come down to luck? For you to be in this school and me to be here. And have a computer sitting right in front of me. For the lights to work, and the heat actually is on. That shouldn’t be a matter of luck, should it? I certainly feel as an educator, everyone needs people who are dedicated to their craft. I’m lucky to be doing it here.”

History is well-acquainted with inequality. History is what Dr. McKenna trademarks as “an evidence-based argument,” but is also a sentimental social science, baring the ugliness of the past. But for Dr. McKenna, the past and future are not mutually exclusive. “The people who are the most forward-thinking are most connected to the past,” he muses. “Because there’s an honesty in the past that is going to inform how you’re moving forward.”

The Ancient Romans worshipped a god named Janus, associated with doorways, transitions, and beginnings and ends. He is depicted with two heads, one facing the past and the other facing the future, stern and stoic. This is how Dr. McKenna taught me to view history, a double-edged sword of time, diligence to two expansions of time, going opposite directions.

“Make your dent in the corner of the world in a positive way,” Dr. McKenna tells me. “The individual is so powerful. History is full of that. Individuals who made an incredible impact. So don’t underestimate your powerful, positive change.”

And the Goethe quote on his bulletin? If you treat an individual as he is, he will remain how he is. But if you treat him as if he were what he ought to be and could be, he will become what he ought to be and could be. The past, present, and future.

Enya Xiang '21 is thrilled to return as Opinion Editor, this time co-editing with Sammy Biglin! She is excited to see what controversies and 'hot takes'...